Pattern Recognition

A few years ago, Max Lamb had to fill 100 square meters of floor. The occasion was his 2016 exhibition Exercises in Seating at the Villa Noailles, designed by Robert Mallet Stevens. It was a great opportunity but a daunting one; “100 square meters of rugs,” as Lamb observed, “is a lot of rugs.” He decided to immerse himself in the textile industry of Yorkshire, “one of the great British industries that speaks of history, place, geography, climate, culture, hard work.” Ultimately, Lamb’s investigations there led him to develop a multi-site production process involving 420 kilograms of custom-made thick yarns, which were then space-dyed (that is, printing different colors along the yarns) and machine-tufted. The result was seemingly infinite variegation, which organized itself into broad stripes - a carpet-landscape, like something seen from an airplane window.

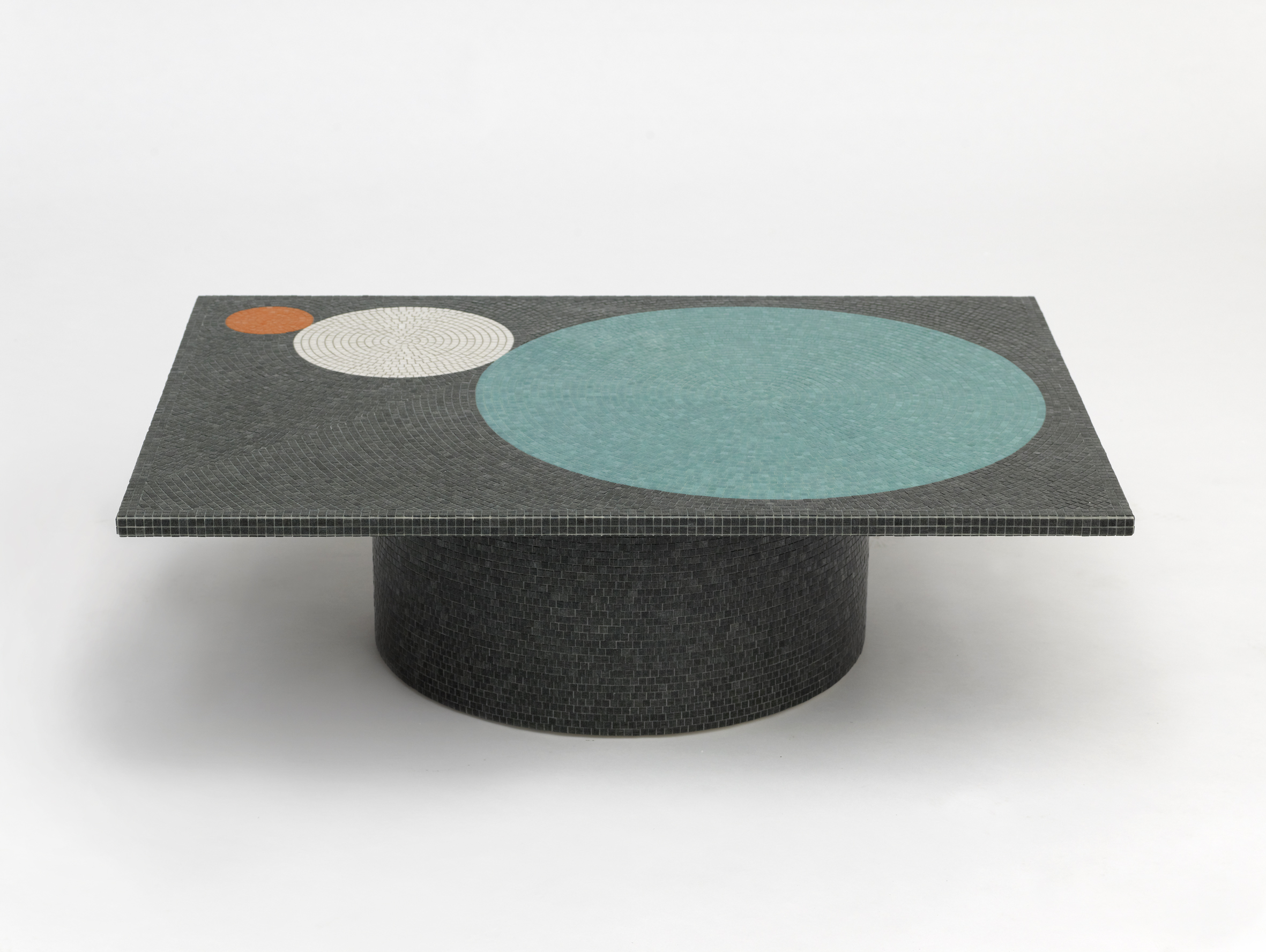

Here we see one rug from that project, alongside works by the designer Pierre Charpin and the ceramist Andile Dyalvane. Pattern, of course, is one of the key terms in design discourse. Though often relegated to a secondary status (considered to be “mere” decoration), it is also a field of endlessly ramifying complication, which can be explored forever but never mastered. Charpin’s table is a perfectly satisfying composition, just three graduated circles. But simple as it is, it implies infinite progression in either direction.

Dyalvane’s open vessel does something similar spatially, with a cascade of arcing forms articulating its wall. This telescoping composition can be related to the artist’s intentions in creating the work, as an emblem of the expansive South African landscape and his own familial lineage. Of the titles of his work, such as OoJola, he has said: “The names are stories, limbs in a way of a much bigger story that tells of a place, its families, people and community.”

DNA is a collaborative essay project, intertwining three gallery programs into a single, generative presentation.